It’s easier to look at your skin (excerpt from channel one) from Blinky on Vimeo.

It’s easier to look at your skin (excerpt from channel two) from Blinky on Vimeo.

FEMININE | MASCULINE

essay by MATTHEW SHANNON

See what you wanna to see

Do what you wanna to be

Be where you wanna to be

– Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, Alien Brain.

Belle Bassin’s work comes from the folded, affective logic of dreaming. To consider the work in Feminine Masculine is to give thought to how we are visited by images in the 21st century and where it is they come from. Are they an ingression or egression? And, if it’s a case of both, how does this double movement function?

Andre Breton, author of the Surrealist Manifesto, called for the creation of what he termed ‘dream objects’. These were portable manifestations of the unconscious, largely in the form of image/object/text collages. Breton called for such objects to be widely produced as part of a practice that would connect waking life to dreaming. These objects would not be considered artistic in themselves, quite the opposite. Rather than existing in the suspensive mode of art, where life in the world is reflected upon and refracted into an artistic work; the dream object was intended to allow the inhabitants of a modernised, industrialised and rationalised Western hemisphere reconnect with a more primitive way of being.

Historicism aside, the ‘dream object’ is significant in its attempt to allow one sphere of being to pierce another. They act as the tip of a needle that enters into the sphere of rationality. These objects hang, from one domain into another, on the horizon of both.

Breton’s proposal, of course, never became instilled as the cultural practice he imagined. One factor to consider here is that during the post-war period a change occurred in the dominant conception of where ideas come from. By the 1960’s the ‘medium’ had become ‘the message’, meaning that the individual was no longer primarily subject to missives from a subconscious reality that had been edited out of modern life. Instead there was subjection to an exterior ‘medium’ that spoke through and moved the individual. The idea of a reality below us (the ‘sub’ of the subconscious) is now accompanied by a new inverted subconsciousness above and around us, now manifest in the ‘cloud’.

The richness and tactility of this exterior has thickened with the technological progress from radio, television and now the Internet and its networked devices. The Internet being such a potent medium it has come to be considered a ‘5th’ domain of warfare alongside sea, land and air by the US military and the Pentagon.

This 5th domain seems implicitly psychedelic (psychedelic comes from Greek and translates to ‘mind’ (psyche) ‘visible’ (Delos)); we are now invited to project our desire for outwards into a domain that can receive our desires and return to us our desires actualised. Just about any image you can wish for will have some analogue on a Google image search.

Here we find a double movement: in one direction we project outwards with a desire that comes from within (a within that could be conscious or subconscious or both) and in another direction an anterior and exterior of moves towards the interiority to meet its projection.

The discussion up until this point posits ‘mind’ as normative fundamental that, although placed in an evolving dynamic, is in and of itself a constant subject to updating variables. Belle Bassin’s work takes this conversation one step further, in that it expresses a will to go beyond the mind itself. This is a difficult proposition to assume easily. If the works are composed by the artist, of materials that make up forms that enter through the senses and are synthesized into unified experience in the mind of viewers, full of associations, memories and interpretations; how can a mind go beyond itself? Is it possible to go beyond the mind if you need to use the mind to do it and be aware of having done it? How can the mind become alien to itself?

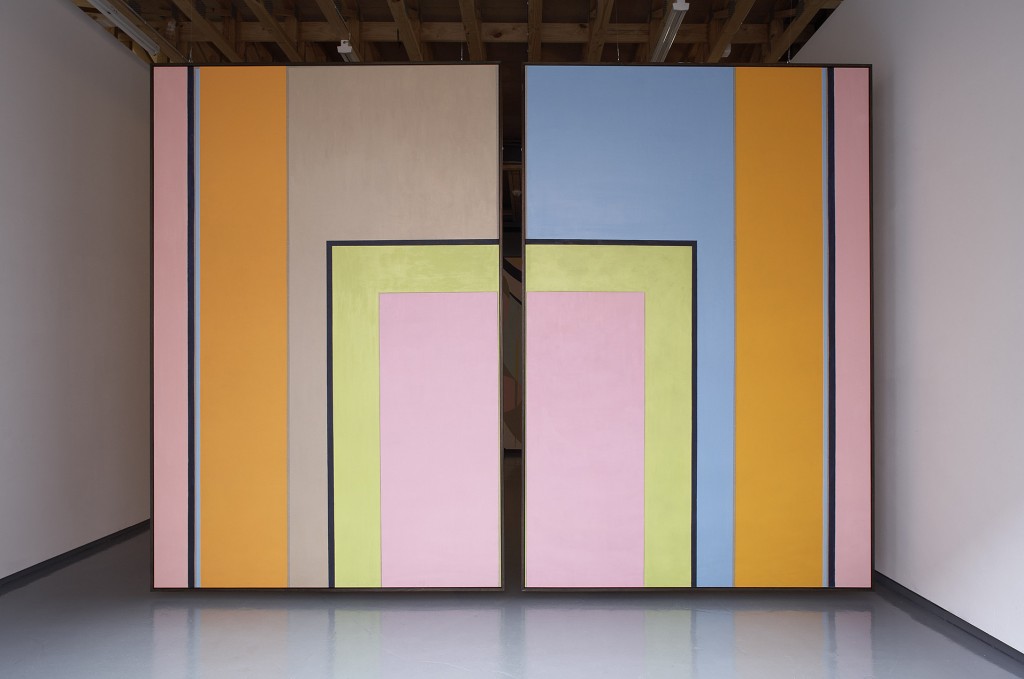

The folding doors in the eponymous work Feminine Masculine bring us towards this position. Feminine Masculine and The Folds use architecture to suggest that a passage through the limit of mind will structurally alter both what is around and in the traveller. The doors will not open – but fold, inverting the relationship of inner and outer; like the tangled hierarchy of the Mobius strip – a plane with only one side.

This twisted singularity is an expression of the affective logic of the psychedelic, where the waking world is reconciled with its other in a constant energetic emanation. The feminine and masculine fold into one another, reminding us of Walt Whitman’s Poem Unfolded out of the folds:

Unfolded out of the folds of the woman’s brain come all the folds of the man’s brain

Once folded, the differential of Masculine-Feminine, Mind-World become obsolete. And, further more, to be able to adopt this position as a perspective, it could be argued, gives access to the possibility of an alien mind; a perspective of pure hybrid differences. This maybe an avenue to overcoming the contradiction of how a mind, once alien to itself, could still be conscious of its own condition of existence.

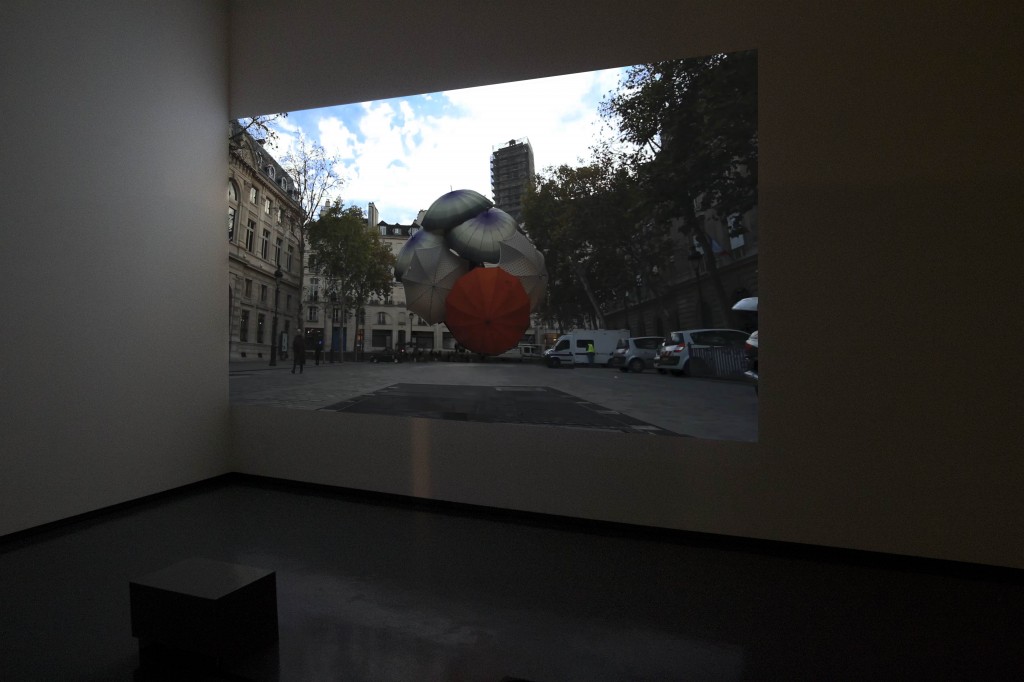

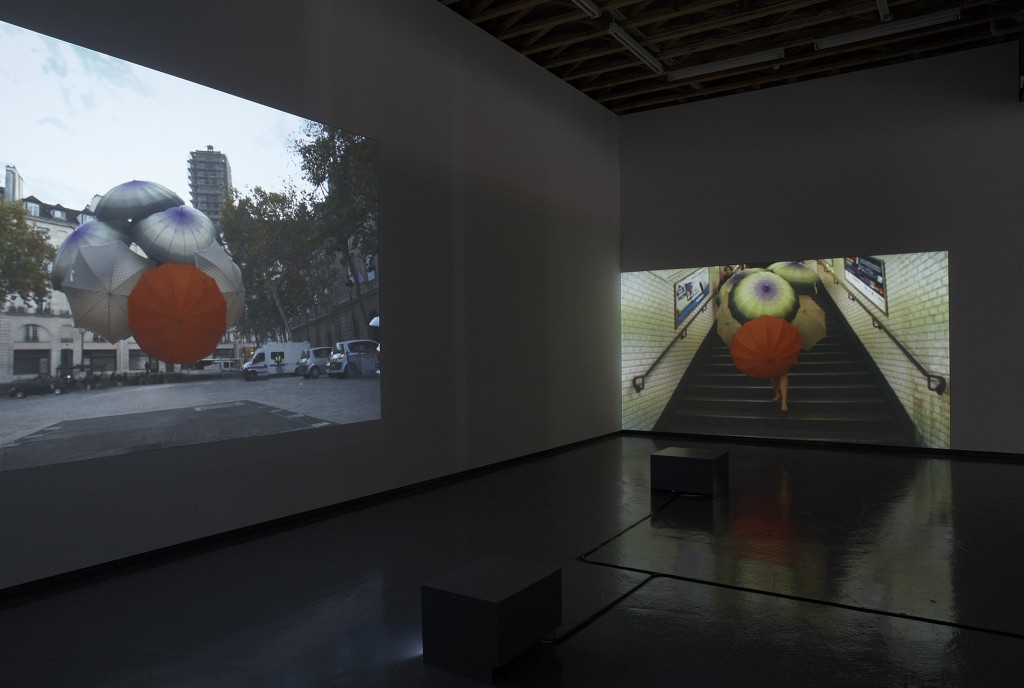

The works Masculine Feminine and The Folds give a context for It’s easier to look at your skin. In this Video work we see a living sculpture navigating Paris streets and metros. This entity (inhabiting the video as a city) is part animate and part inanimate matter, part human part umbrella. What is the mind of this entity? From what perspective does it view its exterior? Is it human? Probably not, is it alien?

—

Belle Bassin would like to acknowledge and thank:

Dario Vacirca, Anna Tweeddale, Whitney Lorene Wood, Kate Scardifield, Melissa Bamford, Mila Faranov, Andrea Jolley, Evan Lorden, Jess Hewett, Pete, Teresa Tweeddale, Angie Manifavas, Renato Vacirca, Rose Mastroianni, Matthew Shannon, Tamir Zadok, the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Arts South Australia, Cite Paris and Fehily Contemporary.

© 2025 The Door | rejigged by TIMSON creative