The terror of n………..

n

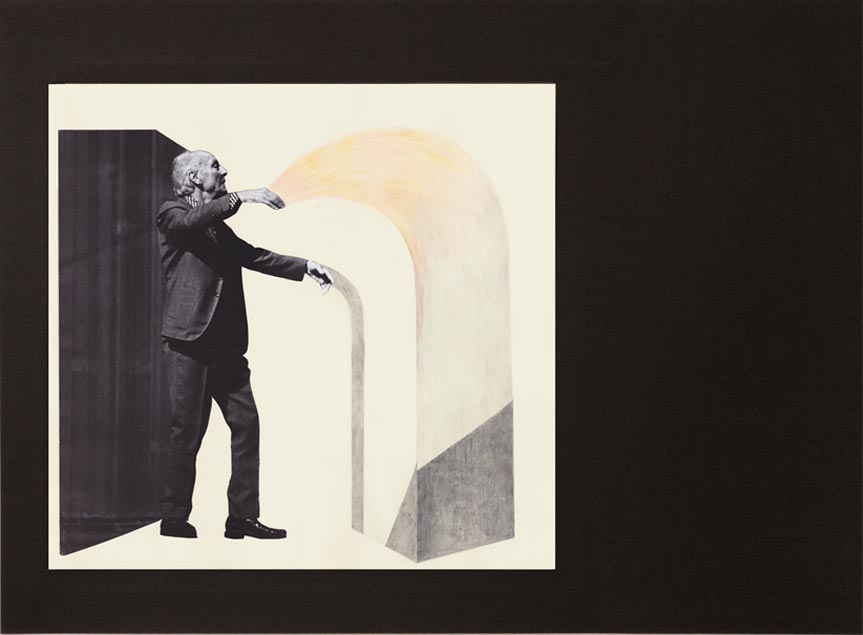

The Terror of n

O

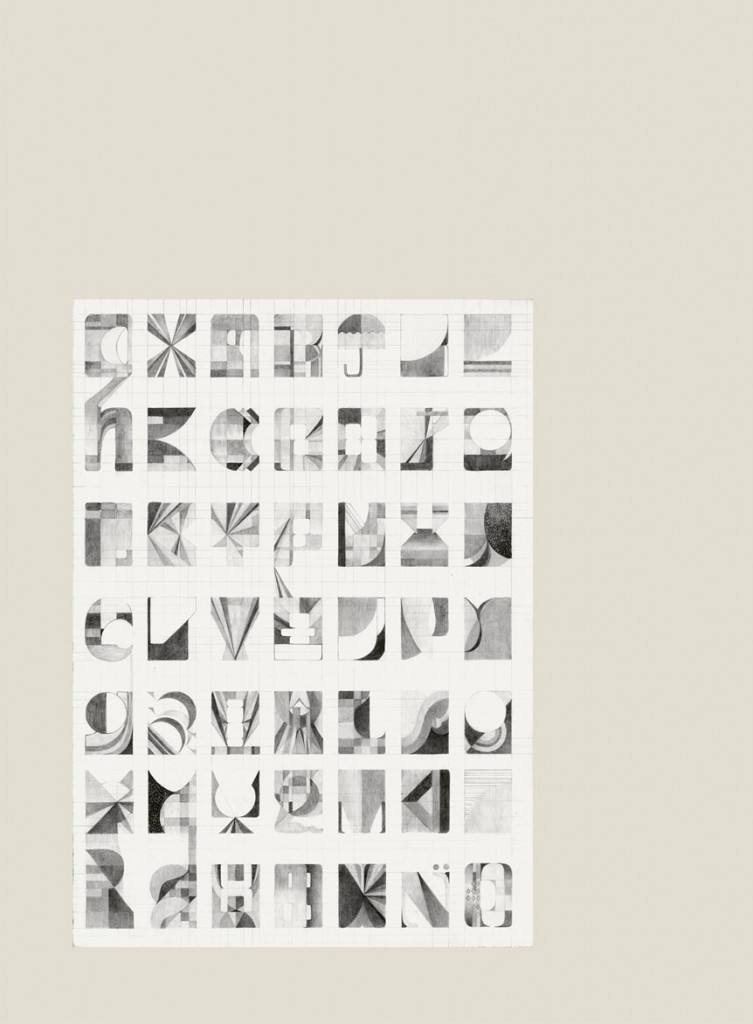

Complicit Font

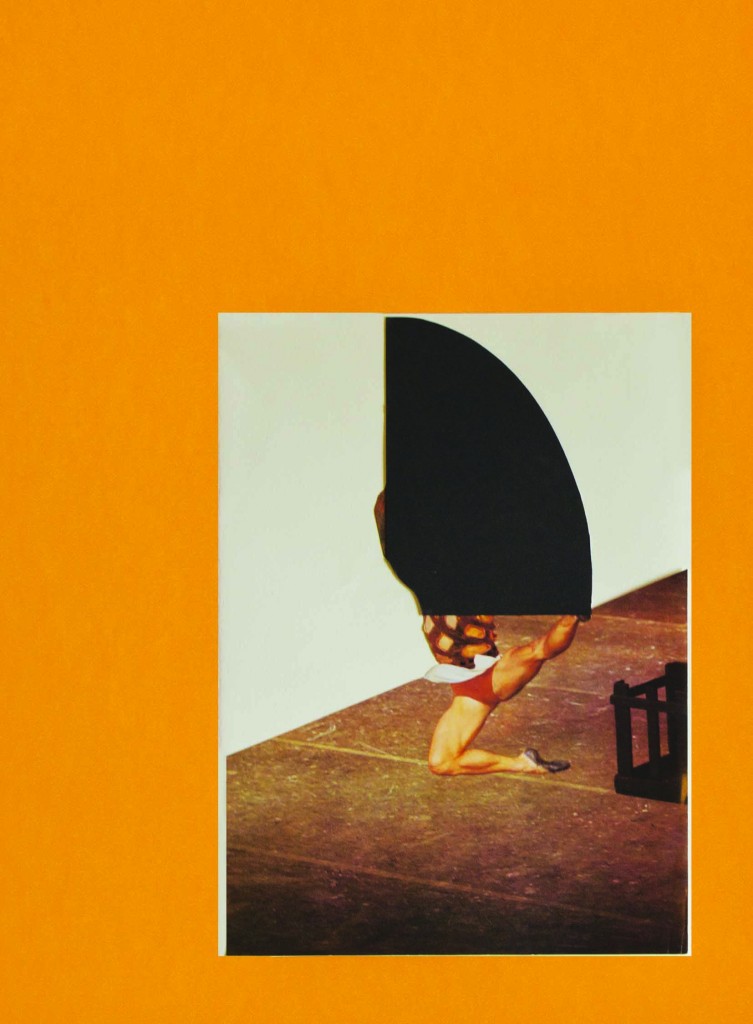

Untitled

Untitled

Photography, collage and pencil on paper

Suite of (6) drawings

Private collection

Work from this series was included in ‘drop caps’ viewable here

or in this book by Sternberg Press

writing

———————————————

ON STAMM by Mila Faranov

In both style and content Belle Bassin’s recent solo exhibition, The terror of n, has a strong resonance with the work of 19th-century spiritualist artist Hilma af Klint. Both artists employ geometric abstraction, meticulous grid work and esoteric symbology that belie the formality, order and control implied by such approaches, instead quietly moving toward an unknown coda and potentiality that suggests a sort of transcendence.

Theosophy refers to systems of speculation or investigation seeking direct knowledge of the mysteries of being and nature. John Golding called theosophy ‘a world of vast, intangible and amorphous ideas’. In a sense, both artists attempt to portray enigmatic elements of parallel and invisible realms. Af Klint was considered a clairvoyant, claiming that her work was guided through a psychic connection on another plane. While Bassin’s work may not have been created in this way, it certainly speaks (albeit mutely) to interpretations and connections with and of multiple dimensions.

Nostalgia pervades Bassin’s work. There is a graphic sensibility that recalls the era of psychedelia and esotericism. In particular, The terror of n is reminiscent of a Luis Buñel film from the ’60s; the spectral O is a potential gateway to an elsewhere in which a gentleman appears as a sort of guide, cut from the books of another era. The work’s paradox implies a vacuum; the suspension of time and suggestion of movement.

Bassin’s work is an exploration of semiotics. The idea of mute language—a forever not quite narrative—is a central theme. Obscured movement and the frozen gesture reinforce the idea of semantic flux. The artist has created a world of limbo and potential where symbols are at once more than what they seem, yet not quite what they appear to be. Complicit font, an almost-alphabet of pictograms, seductively plays with this notion.

The exhibition itself is a tableau that simultaneously diverges and digresses to create a multitude of possibilities. In this way Bassin inspires the need for an interpretation but then disables one. It is precisely this disruption of flow that enables the viewer to search for a new one.

Belle Bassin, The terror of n, Fehily Contemporary, Melbourne, 9 February – 3 March 2012.

Online Journal → Stamm

———————————————

ODE TO FORMATION

by Simon Maidment

When you position them they either have to say – on or no. I like both of these as they are really the same thing in different contexts, but I do love a good no, and a good on. [i]

No proclamation. You have to look and you have to take it in.

This man, he has learned, become learned. Not a master, there’s no ownership, but a productive medium this man, between planes and flows.

He has learned to recognise and engage a vast abstract realm of simultaneous possibility. Acutely aware and deft, able to craft a specific event from the prismatic potentiality, see what happens if one was to do that, but like this, now follow me.

The identity of the person depicted in the collages by Belle Bassin is perhaps not important, though the specificity is, his age, his gesture, his poise. I sat and stared at the images, until discerning they depicted the same man, at once in a temporal flow that the single image depicts, and in a doubling of that flow, as he ages between the works. I sat and stared and thought hard about accumulated knowledge and the deftness of his insertion between a virtual and actual planes in the event of his movement, how we see that he is both ‘tapping into’ and ‘producing’ these events.

I sat, staring and thinking, about how much they resonated with, and clearly they appeared to me to imply, a theorisation of the world described by Deleuze as a relation between the virtual and the actual. About how the works could be read so precisely as diagrammatic, in their depiction this man smoothly making actual one of the innumerable possibilities of what could happen at that given moment. Possibilities which are, in this schema, going on simultaneously, all together in their multitude at that very moment in the virtual, which Brian Massumi describes as ‘a form of superlinear abstraction’.[ii] Free will, he writes in that essay, is subtractive, ignoring the autonomic potential of doing all of those other things, in all of those other ways, that our body is on the verge of enacting, but allowing it to do this one thing, just like this. Thus our stillness is a perpetual refusal of the potentials that abound (this is Belle’s ‘no’), and a subsequent decision to do doesn’t create something in place of nothing, instead, allowing something already there to find form (yes, we’re ‘on’). Thinking in this fashion one cannot help but recognise the precision of this man, his posture and the self-assured movement – and marvel at the radiance he summons and Belle translates for us to see.

To be explicit to the theme of the exhibition here, one could argue that the belief in the existence of a plane, where a seething mass of everything-about-to-potentially-happen-all-at-once is occurring in relation to us, would seem aligned with the Romantic Movement, with their rejection of the Enlightenment’s universal order, the rational (or as Henry Adams put it some time later: ‘Chaos is the law of nature; order the dream of man’). A number of others have taken the discourse further,[iii] forging an explicit link between Romanticism and the work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, including the obvious link between the Romantic celebration of nature (over culture) and Deleuze and Guattari’s writings on ‘becoming-animal’ in A Thousand Plateaus.

There is a question though, and this is directly related to considering this man Belle presents us, as to whether the understanding of the self is similar. He embodies an intense sense of self, that much is clear, and in considering these works by Belle I do have a sense of a rejection of any universalising system – both by the subject and author of the works – with instead movement and individuality coming to the fore. Again, in reference to the exhibition’s field of enquiry, we can ask whether this subjectivity has been forged in the intense exploration of the radical individualist spirit we associate with the Romantic movement and philosophy, or one entwined with, and in relation to, a community of others, still engaged with the world(s) of others.

This man’s acts of ‘tapping into’ and ‘producing’ recall for me the notions of subjectivity Guattari argues for in ‘The Three Ecologies’, subjectivities that are produced within and between relational fields. In this extended essay Guattari rejects an understanding of the self that is a structure imported from elsewhere, and instead, like Deleuze, insists that it is actively generated, over time. Guattari argues that relationship to context is crucial in the development of a practice of life that takes in the enormity of the contemporary world, its issues, power structures and the desire to do and be better. In what he terms an ecosophy of life, an ‘ethico-political articulation’, he identifies environmental, social, and subjective registers as three intertwined fields of relations that need to be engaged with together. Here engagement with ‘the rest of the world’ and with the active production of subjectivity is fundamental: ‘Instead of clinging to general recommendations we should be implementing effective practices of experimentation, as much on a microsocial level as on a larger institutional scale’.[iv] This is a call to form new practices and subjectivities, to distance ourselves from normalized subjectivity via ‘singularization’ (which is to say a movement towards heterogeneity and away from the homogeneous models held in place by what Guattari terms ‘International World Capitalism’).

Let us think on this in relation to William Blake, and his often recalled quote ‘I must create my own system, or become enslaved to another man’s’. Thinking these two together, perhaps Félix Guattari’s call to ethico-political action is less a departure from our nostalgic notion of Romanticism than if taken at first glance.[v] Instead of radical individualism, perhaps reimagining of subjectivity today, if it is to be radical, emancipatory, and engage freedoms, requires a small evolution towards individuation in groups and communities, rather than strict individuality. As Guattari writes: ‘Now more than ever nature cannot be separated from culture; in order to comprehend the interactions between ecosystems, the mechanosphere and the social and individual Universes of reference, we must learn to think “transversally”.’[vi]

To look again at these work by Belle with these ideas shimmering in the background. She brings her own aesthetic of quietude, and, as mentioned before, radiance, to this these images, as ‘post-minimalist’ as they might be described. My sense looking hard is that we’re not presented with an irrational ‘universe’ of an individual, but instead a glimpse of an order – not yet instrumentalised – and its translation into a realm where it becomes form.

To the identity of the man depicted. He was a ballet dancer who also studied music extensively. He choreographed his first work at 16, his first with Igor Stravinski at 24, and dedicated his life to that craft after an injury ended his performance career. He was a Russian exile who founded, in 1934, the School of American Ballet as a first step towards becoming the co-founder, ballet master and principal choreographer of the New York City Ballet. He held those positions until his death in 1983, aged 79, at which point he had choreographed 466 works, along with films, operas and musicals. He is credited with revolutionising the look of classical ballet in rejecting his homeland’s focus on narrative, instead believing in the potential of movement itself. He is George Balanchine, among the most influential choreographers in history.

[To focus on manoeuvring in the uncertainty of a situation] gives you the feeling that there is always an opening to experiment, to try and see. This brings a sense of potential to the situation. The present’s ‘boundary condition’, to borrow a phrase from science, is never a closed door. It is an open threshold – a threshold of potential. You are only ever in the present in passing.[vii]

×

Simon Maidment is Curator, Contemporary Art at the National Gallery of Victoria, and a media-based artist with a practice that often involves collaboration, curation, and writing.

[i] Belle Bassin, in correspondence with the author, 2012.

[ii] Brian Massumi, ‘The Autonomy of Affect’, Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), p.31.

[iii] David Baulch, Peter Heymans, Toby Austin Locke, Martin Procházka, John Sellars et al.

[iv] Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton (London; New Brunswick, NJ: Athlone Press, 2000), p.34-35.

[v] Indeed, Martin Procházka argues in his book Transversals that, Deleuze’s ontological attempt to replace the conscious subject with a subject-through-time is, according to his reading, closely linked the notion of the subject the Romantic movement set in train, one capable of defining itself by its ‘creative potentials rather than its conscious experience of itself’.

[vi] Guattari, op. cit., p.43.

[vii] Mary Zournazi and Brian Massumi, ‘Navigating Moments – with Brian Massumi,’, in Hope: New Philosophies for Change (Annadale, NSW: Pluto Press, 2002), p.212.

Online Journal → Ode to Form

© 2025 The Door | rejigged by TIMSON creative